Submitted by Sarah Bailey on Fri, 19/03/2021 - 14:01

The relationship between food consumption and physical activity is an important one, particularly for researchers looking into food consumption patterns in relation to nutritional balance. Here, Flagship Project 1 Research Associate Astha Upadhyay from TIGR2ESS collaborator PRADAN shares her recent experience using activity monitors in the community she researches in Chakai, Bihar.

Why do we eat food? Why is it so important for life? What happens inside our body when we eat food? These are questions many of us would have asked during our childhood. But as we grow older, we realize how the food we eat matters a lot.

The foods we consume acts as a fuel, providing energy for our bodies. The nutrients and micronutrients they provide in the form of carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and fiber play vital roles in human health and growth and the prevention of several diseases. However, achieving and maintaining balanced nutrition is still a central challenge for global health.

Status of health and nutrition in India

The latest edition of the Global Nutrition Report (GNR), 2018, states that malnutrition is unacceptably high across the world. In India, the situation is even worse. With 14% of the population undernourished, India is in the ‘serious’ hunger category (Global hunger Index report, 2020). States such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh greatly affect the national average. These states are densely populated and have high levels of malnutrition. The GNR also states that women carry a higher burden than men when it comes to certain forms of malnutrition: one third of all women are anaemic, and millions are still underweight.

In a 2011 report, the Indian National Institute of Nutrition states that the major areas of concern are an insufficient or imbalanced intake of foods or nutrients; widespread malnutrition is largely a result of dietary inadequacy and unhealthy lifestyles. Therefore, a variety of foods, including traditional and forest foods which are readily available, can be selected to formulate nutritionally adequate diets whilst preserving knowledge systems about food that would, without support, otherwise be lost.

TIGR2ESS is collaborating with PRADAN to achieve a shared goal

The TIGR2ESS programme revolves around the idea of improving lives and livelihoods to support better health, nutrition and economic outcomes. At PRADAN we use our intensive grassroots connection, working directly with communities, to achieve improved health and nutrition. We carry out research in communities to inform decisions about how to achieve these shared goals.

Therefore, the aim was to understand the traditional current dietary practices of the Santhal tribal community in Chakai block of Jamui district in Bihar state.

Accelerometer devices

An accelerometer is an electromechanical device used to measure acceleration forces. There is a strong relationship between the food we consume and the degree of physical activity we undertake. Hence, in our study, we used Actigraph to measure the energy expenditure by capturing movements in three planes (left, right and frontal bend).

Initiating the process

The idea of using accelerometers in our research project emerged from wanting to understand the direct relationship between food intake and energy expenditure among communities at our study location, Chakai, Bihar. The study was conducted with the help of two enumerators: Kusum and Sonalal.

Our visit to ICRISAT, a collaborator on the TIGR2ESS project, gave us an opportunity to learn how the Actigraph device is used in their projects. Their study protocol involves simultaneously monitoring data collected on the device, the Actigraph, while collecting data on participants’ energy and consumption. We were therefore also trained in time-use sheets to map out 24 hours of activities and food consumption using 24-hour dietary recall. Data collection is accompanied by participant observation, which requires full-time engagement from enumerators – dedication is needed.

The challenges of adapting new technology to a rural community

While planning how to execute the study in our chosen communities, several pragmatic realities and constraints came to light. We found it was not possible to replicate the study procedure used by ICRISAT in Chakai because of great differences in terms of both institutional resources and food consumption practices.

The training our enumerators went through was based on the eating habits of the ICRISAT study site, which differs from the people of Chakai. One major difference is units of measurement. Communities in Chakai have local measures like pyla and dubu. The ICRISAT protocol involves giving participants utensils to eat to help the researchers estimate quantities of foods by using a standard unit of measurement. One of the tenets of our community-based research is not to impose our ‘things’ on the participants; this made using ICRISAT’s study protocol impossible because if we prescribed utensils to participants we would change their way of their eating and so their consumption pattern. Hence, the study had to be redesigned to accommodate these differences.

Many people had doubts about how the accelerometer was going to be used: Will it be something to wear? Will it cause any abnormalities in the body? Or could it be a blood-sucking device? People were suspicious that the Actigraph may contain explosives and blow them up.

One enumerator, Kusum, was quite apprehensive about asking about food consumption and suggested these questions were removed from the questionnaire. She felt that no one would say what they eat, especially to an outsider:

“They [respondents] will eat [one] thing and will tell [us] something different, and when you match the data, it won’t make any sense. Similarly, with the activities they do, they will not tell [us] correctly.”

Where and how was the study conducted?

We carried out the study in two villages of Nawadih panchayat: Govindpur and Naiwadih. We chose this panchayat as it was the end of December and Nawadih, having plain and rolling topography, was the only TIGR2ESS panchayat where farmers were still involved in harvesting paddy. This meant we would be able to clearly identify and map different activities where energy expenditure would vary.

We recruited five individuals to take part in the study. The participants were told to wear the device just after they wake up in the morning, from 6am, and remove it before going to sleep. Our enumerators were available to check and to remind participants.

We collected data from several sources: time-use sheets to map out 24 hours of activities; food consumption using 24-hour dietary recall; participant observation; and Actigraph data.

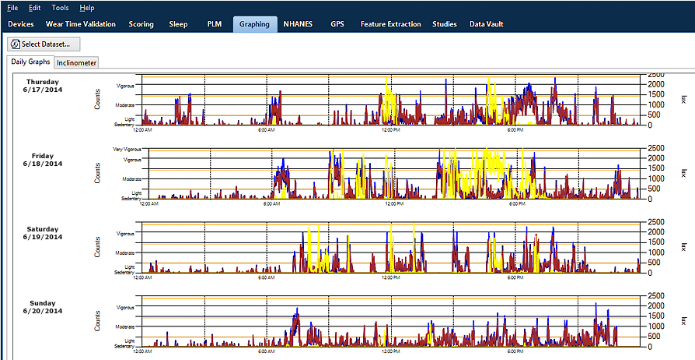

Graph showing variations in the rate of energy expended while working. A higher peak indicates a more laborious activity meaning greater energy expenditure.

There are major differences in activity and food consumption between men and women

When we analysed the results of the study, we found substantial differences between men and women.

In terms of consumption: there is no fixed time for women to consume meal but for men, the time-interval is fixed. Women preferred green leafy vegetables, rice, kurthi pulse and men preferred vegetables such as: cauliflower, potatoes and tomatoes, in addition to the foods women consume. The quantity and variety of food consumed also differed, with men eating bigger quantities and more varied foods than women. Men, apart from food prepared at home, also ate snacks, jaggery (a traditional cane sugar), and liquor.

In terms of activities: women do not consider most of the household work as ‘work’. Around 50% of activities done by women were recorded based on participant observation by our enumerators; women did not think to mention these activities to us. Women showed a diverse and varied range of activities, from agricultural to household chores. On the contrary, men involved in money-generating activities like construction worked for around 8 hours and then no other activities were recorded on their part.

When it comes to work, both men and women are working, therefore, we’ll check and measure that who does more labour. However, men do much more labour or work than women. They plough lands and do much heavier work than women do.” Kusum, study enumerator.

This is a common notion around ‘work’ in the village. The time-use data also revealed that only men travel for recreation or leisure.

What next?

Following this small pilot study, we have identified several areas we could improve our methods and new research questions that have arisen.

Providing further training would be very useful. For example, our enumerators can be further trained to conduct more scientific studies and surveys, using the Actigraph and other methods. Building the skills of Santhal [tribal] youths to undertake research work would also be helpful as they could work as local research assistants with minimum language barrier. We can also enhance our statistical and organizational expertise for similar future studies. We envisage creating a pool of research staff adorned with multiple skills to take their own knowledge forward.

We can use the data from this study to answer several important questions:

- To understand the reality versus perceptions around men and women’s working habits

- To understand the patterns of food consumption and activities both men and women are involved in

- To find out if there are any gaps in nutritional requirements by comparing our data on food consumption with national statistics and, if so, whether these can be overcome.

The next step for us, now that we have data showing a link between anthropometric data and foods consumed and activities undertaken, is to take the data we have collected back to the study participants to begin working towards behavioural shifts by increasing knowledge and awareness. We are looking at various ways to take this forward; we are planning to promote locally available food items along with their nutritive values and we are seeking help from nutritional experts from TIGR2ESS collaborator NNEdPro. TIGR2ESS has provided a platform to support such cross-site and cross-institutional approaches which we hope will be fruitful for our future work.